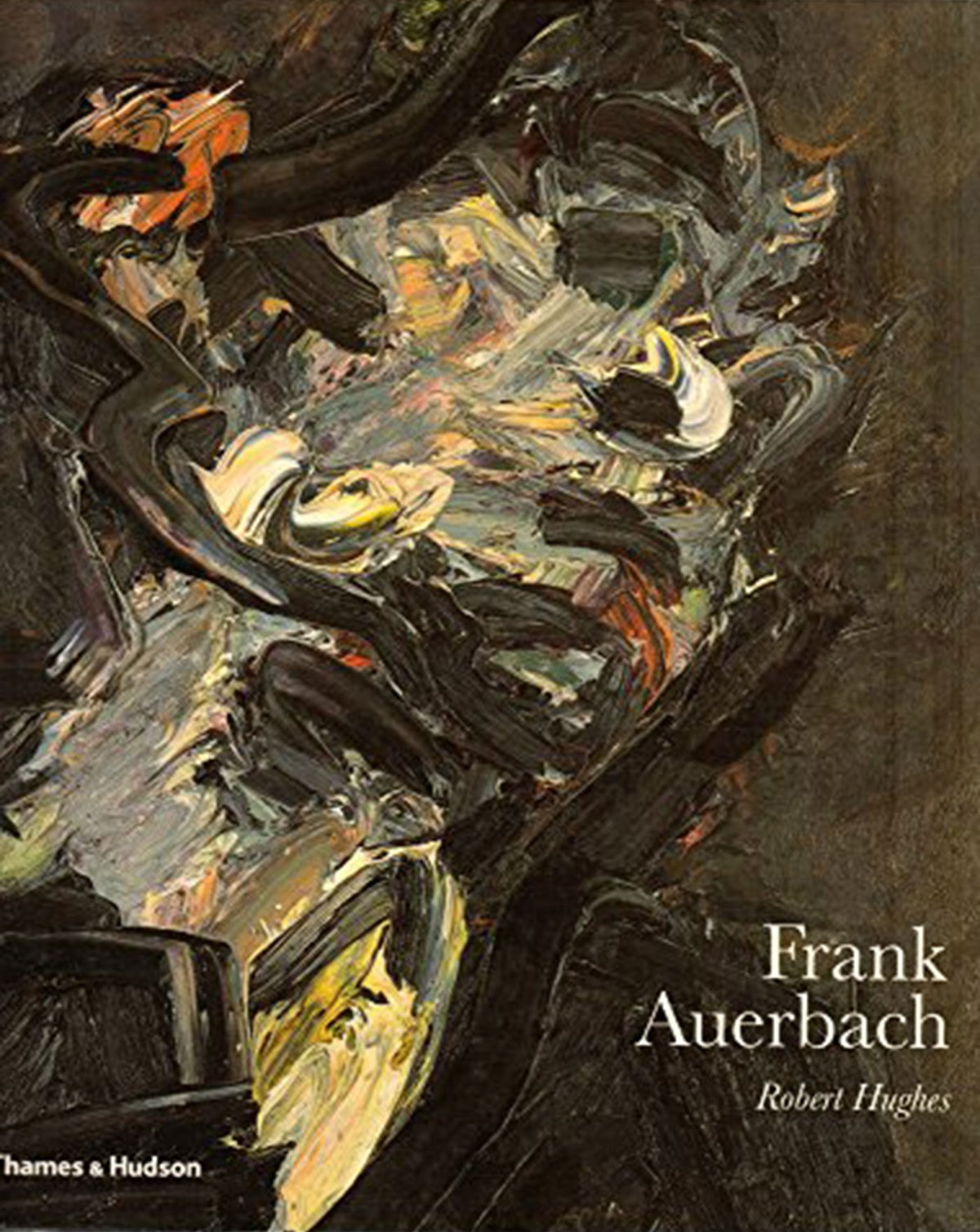

Frank Auerbach's paintings and drawings have never been so well publicised or so fashionable. The Saatchi Collection has had a show for much of this year and this autumn sees a new series of etchings and an exhibition of recent paintings at the Marlborough Fine Art. But most significant is the publication of the first book on the artist, Frank Auerbach, by the writer and critic Robert Hughes. Hughes, of Shock of the New fame, has increasingly championed English figurative painting. He recently proposed Lucian Freud as the world’s finest living realist painter and now hails Auerbach for representing a way forward for modern painting through his exploration of man’s "relation to the real, resistant and experienced world".

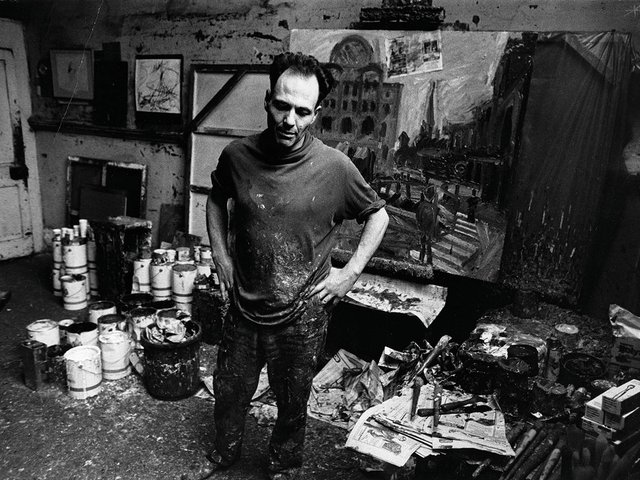

After early scene-setting chapters which include evocative descriptions of Auerbach’s studio and working practices — already the subject of much mythologising — Frank Auerbach is broadly chronological. Emphasis is firmly on the pictures themselves and Hughes skilfully charts Auerbach’s stylistic and thematic development.

Appropriately, the book is dominated by its beautiful illustrations and it is exciting to see so many works reproduced for the first time.

The colour plates are a triumph considering the difficulty of photographing the often thick paintings, while the extensive use of duotone proves especially suited to reproducing the charcoal drawings. Particularly fascinating is a sequence of forty images revealing the radical changes made to Portrait of Sandra, as session by session, lines were built up and rubbed down. The accompanying text does not set out to be an objective, detached biography or a critical commentary. Instead Hughes has provided an extended essay that is broader, more literary and discursive. It is at its best when describing Auerbach’s early years, revealing the artist’s response to the work of others and discussing his working procedure. Interviews with some of the artist’s models are also especially useful.

Hughes gives centre stage to lively extracts from correspondence and interviews with the artist; these prove to be as eloquent as the paintings are exhilarating, characterised as they are by their breadth of reference whether to painting, literature or poetry. The temptation to rely on these must have been great and, besides an extensive use of direct quotations, the familiarity of some of Hughes’s analogies suggest they, too, come from the artist.

This makes for an enjoyable book, but if there is a criticism, then it is this very dependence on the artist for interpretation. Given Hughes’s justifiable focus on the works themselves, his reliance on Auerbach’s own perception, though successful in providing an insight into intention, sometimes falls short in addressing impact. Indeed, on occasions attention seems to shift away from the paintings and to the artist’s observations. These, though often analytical, do not always do justice to the pictures themselves. They sometimes rationalise and even obscure Auerbach’s achievement.

Hughes discusses early critical consideration, when, in the light of Abstract Expressionism, focus usually lay on paint surface and emotion. He chooses to emphasise “the immediacy of experience, fidelity to the subject and search for an underlying structure”. In so doing he reflects a new orthodoxy based on Auerbach’s own conception of his work as observational, architectural, even classical. Perhaps more relevant for the viewer is direct discussion of what Auerbach has produced; it is indeed a strange hybrid.

Hughes, for example, cites Auerbach’s admiration for Picasso’s pre-Cubist conceptualising of form. But though the drawings of both do attempt to build from an underlying structure this does not address the particular power of Auerbach’s work. It has a charge, a spark, an energy. It is exciting because it is daring, inventive, even idiosyncratic; gesture plays an important part, work is finished in the crisis of a moment. But, despite the bravura of the performance there is a remarkable composure.

Auerbach’s surprise that at his early shows people drew attention to the paint, is reported, but Hughes is less informative about how the paintings do actually reward sustained scrutiny. Standing in front of an Auerbach, one is almost aware, at first sight, of the paint texture, the colour, the way the surface is worked. The response is sensory.

Auerbach’s work ...has a charge, a spark, an energy. It is exciting because it is daring, inventive, even idiosyncratic; gesture plays an important part, work is finished in the crisis of a moment. But, despite the bravura of the performance there is a remarkable composure

Although one may glimpse the subject, it is often only with prolonged attention that the details emerge. There is economy of form, a use of ciphers, that mean, despite Auerbach’s gestural handling of paint, that there is a startling richness of subject detail. There is a moment at which a painting clicks, an instant when the viewer’s admiration for colour and general understanding of form gives way to a sudden grasp of specifics such as gender or place. The colour plates provide a striking example of this. In The Sitting Room (currently on display at the Tate Gallery) one first gains a sense of the space of the room, feeling one’s way around it. One reads the walls, the window, a lamp, a chair, the framed photographs and the pictures on the wall. Then suddenly, surprisingly, areas of colour become people; readable and obvious.

In a flash the painting comes to life; an epiphany in which experience of the material stuff of paint on canvas gives way to the revelation of a new world. This is what is so exciting, so daring; the risk that a painting may never cohere; that it may remain a series of ciphers; that its language may remain, forever, private. The particular, startling way that such a painting rewards attention makes discussion of the legacy of Sickert’s interiors seem somehow irrelevant.

However, all in all, this is an exciting book. The production is exceptional and Hughes’s writing is marvellously readable, but perhaps, a riskier path would move on from charting evolution or suggesting affinities to exploring the mysterious relationship between picture and viewer.

- Robert Hughes, Frank Auerbach (1990, Thames and Hudson, 240 pp, 254 ills., £25).

- Frank Auerbach: Recent Work, Marlborough Fine Art, London, until 29 October 1990